After this part you'll know about:

import this

The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters Beautiful is better than ugly. Explicit is better than implicit. Simple is better than complex. Complex is better than complicated. Flat is better than nested. Sparse is better than dense. Readability counts. Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules. Although practicality beats purity. Errors should never pass silently. Unless explicitly silenced. In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess. There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it. Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch. Now is better than never. Although never is often better than *right* now. If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea. If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea. Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

def count_word_lengths(text):

words = text.split(" ")

all_word_lengths = []

for word in words:

word_length = len(word)

all_word_lengths.append(word_length)

return all_word_lengths

count_word_lengths(

"Programming in Python alleviates executing your research ideas very quickly"

)

[11, 2, 6, 10, 9, 4, 8, 5, 4, 7]

print("Hello World")

Hello World

Done 🤗

print is called a function.

The print-function takes in data and writes it the current output.

print(0, 1, 3)

print("A", "B", "C")

print(0, "A", 1, "B", 2, "C")

0 1 3 A B C 0 A 1 B 2 C

from time import time

print("Current unix timestamp is", time()) # <= The time-function does not need any input,

# but steel needs round brackets to be evoked!

print("Current unix timestamp is", time) # Otherwise, the result will be meaningless...

Current unix timestamp is 1667892896.643146 Current unix timestamp is <built-in function time>

my_data = 0

print(my_data)

0

my_data = 1

print(my_data)

1

type-function takes in any variable and returns the datatype of its current valueprint(type(my_data))

<class 'int'>

my_data = "Hello World"

print(type(my_data))

print(my_data)

<class 'str'> Hello World

my_data = "1"

my_number = 1

print(my_data + my_number)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) /var/folders/tx/s3wb7bvx4blgb8xnlhfxvw7h0000gn/T/ipykernel_3250/1373215352.py in <module> 2 my_number = 1 3 ----> 4 print(my_data + my_number) TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

print(int(my_data) + my_number)

2

As we will see later, there are more things than variables that we can name ourselves.

There are conventions for naming a variable to distinguish variables from those other things:

# Wrong:

Number = 1

# Right:

number = 1

# Wrong:

0var = 0

# Right:

zero_var = 0

# Totally wrong:

my first var = 0

# Still wrong:

MyFirstVar = 0

# Right:

my_first_var = 0

# Wrong:

var1 = 100

var2 = 20

var3 = var1 * var2

# Right:

number_of_books_sold = 100

price = 20

revenue = number_of_books_sold * price

Datatypes determine how you can process your data.

You already saw two datatypes in this notebook: Intgeres (-> Whole numbers) and Strings (-> Sequences of characters, (i.e., text)).

But there are (a few) more datatypes:

my_first_integer = 100

my_first_float = 0.1456

print(type(my_first_integer), type(my_first_float))

<class 'int'> <class 'float'>

(1 + 1) * 2 / (2//2)

4.0

print(1 + 1)

print(2 - 1)

print(5 / 2)

print(5 // 2)

print(2 * 2)

print(5 % 2)

2 1 2.5 2 4 1

As you can see by the example 5 / 2, sometimes the result of a computation with two integers can result in a float. This is because python automatically typecasts numerical variables if the results require it.

It's also perfectly fine to calculate with floats and integers, the result will always be a float!

number_of_books_sold = 100

price = 19.99

revenue = number_of_books_sold * price

print(revenue)

1998.9999999999998

# Even if the result could theoretically be stored as an integer without any loss of information.

number_of_books_sold = 100

price = 20.0

revenue = number_of_books_sold * price

print(revenue)

2000.0

As already you saw before, you can also manually typecast your variables.

price = int(19.99)

number_of_books_sold = float(100)

print(price, number_of_books_sold)

19 100.0

Floats can also be properly rounded using the round-function.

approx_price = round(19.99)

approx_numer_of_book_sold = round(100.49)

print(approx_price, approx_numer_of_book_sold)

20 100

message_english = "Hello World. 😊"

message_japanese = 'こんにちは'

message_arabic = "مرحبا بالعالم"

message_ancient_greek = 'Μέγα χαίρετε'

print(

message_english,

message_japanese,

message_arabic,

message_ancient_greek,

sep="\n" # What does this mean?

)

Hello World. 😊 こんにちは مرحبا بالعالم Μέγα χαίρετε

print("Hello.\nDow you know what the \\n character is good for?\n\n\tBest,\n\tA friend of yours")

Hello. Dow you know what the \n character is good for? Best, A friend of yours

newline = "\n"

tabulator = "\t"

# And some others...

longer_text = """

My dear fried,

It has been a hell of a week!

Let me tell you the story of I how REALLY fucked up:

[...]

Best,

A friend

"""

print(repr(longer_text))

'\nMy dear fried,\nIt has been a hell of a week!\nLet me tell you the story of I how REALLY fucked up:\n [...]\nBest,\nA friend\n'

print(longer_text)

My dear fried,

It has been a hell of a week!

Let me tell you the story of I how REALLY fucked up:

[...]

Best,

A friend

message = "Hello "

name = "Lennart"

print(message + name)

Hello Lennart

print(f"Hello {name} 1 + 1 = {1 + 1}")

Hello Lennart 1 + 1 = 2

Especially, if you do NLP you often have to process texts stored as strings (tokenizing, cleaning, etc.).

Luckily, Python provides many methods (i.e., functions directly bound to a string) to help you with that!

print(*[m for m in dir("") if not m.startswith("_")], sep="\t")

capitalize casefold center count encode endswith expandtabs find format format_map index isalnum isalpha isascii isdecimal isdigit isidentifier islower isnumeric isprintable isspace istitle isupper join ljust lower lstrip maketrans partition removeprefix removesuffix replace rfind rindex rjust rpartition rsplit rstrip split splitlines startswith strip swapcase title translate upper zfill

print("var1".removeprefix("var"))

print("My|spacebar|is|broken|😞".split("|"))

print("123".isnumeric())

print("001110000111111".count("1"))

# Any so much more!

1 ['My', 'spacebar', 'is', 'broken', '😞'] True 9

-> We don't have the time to go through those methods in detail, but your are strongly advised to make yourself familiar with them. They can save you a lot of time!

The best way to go through them is to visit the documentation.

my_list = [0, "1", 2.0, [3]]

print(my_list)

[0, '1', 2.0, [3]]

Lists can dynamically be changed, by:

my_list = []

my_list.append(1)

print(my_list)

[1]

my_list.extend([2, 3])

print(my_list)

[1, 2, 3]

my_list.pop(0)

print(my_list)

[2, 3]

# Actually, my_list.pop not only removes the element at position 0 (i.e., the first element in the list)

# But it also returns it so that you can save it in another variable

new_list = [1, 2, 3]

removed_elemt = new_list.pop(0)

print(removed_elemt, new_list)

1 [2, 3]

my_list.remove(2)

print(my_list)

[3]

my_second_list = [4, 5]

my_super_list = my_list + my_second_list

print(my_super_list)

print(my_list)

print(my_second_list)

[3, 4, 5] [3] [4, 5]

my_list = [3, 1, 2]

my_sorted_list = sorted(my_list)

print(my_sorted_list)

print(my_list)

[1, 2, 3] [3, 1, 2]

my_list = ["Banana", "Ape", "Cat"]

my_list = sorted(my_list)

my_list

['Ape', 'Banana', 'Cat']

my_tuple = (0, "1", 2.0, [3])

print(my_tuple)

(0, '1', 2.0, [3])

But:

my_tuple.append(4)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last) /var/folders/tx/s3wb7bvx4blgb8xnlhfxvw7h0000gn/T/ipykernel_3250/3420063398.py in <module> ----> 1 my_tuple.append(4) AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

Strings, lists, and tuples share two common way of accessing their content: Slicing and Indexing

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

print(my_list[0], my_list[-1])

my_string = "Hello World. 🙄"

print(my_string[0], my_string[-1])

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3)

print(my_tuple[0], my_tuple[-1])

1 6 H 🙄 1 3

Special case for lists:

my_list[-1] = 1

print(my_list)

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1]

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

print(my_list[0:2], my_list[:2], my_list[-2:])

my_string = "Hello World. 🙄"

print(my_string[0:2], my_string[:2], my_string[-2:])

my_tuple = (1, 2, 3)

print(my_tuple[0:2], my_tuple[:2], my_tuple[-2:])

[1, 2] [1, 2] [5, 6] He He 🙄 (1, 2) (1, 2) (2, 3)

Once more, a special case for lists:

my_list[:3] = [0, 0, 0]

print(my_list)

[0, 0, 0, 4, 5, 6]

my_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

print(my_list[:4:2], my_list[::2], my_list[::-1])

[1, 3] [1, 3, 5] [6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1]

in-keyword to search the content¶print(1 in [1, 2, 3])

print(2 in (1, 2, 3))

print("Hello" in "Hello World 😊")

True True True

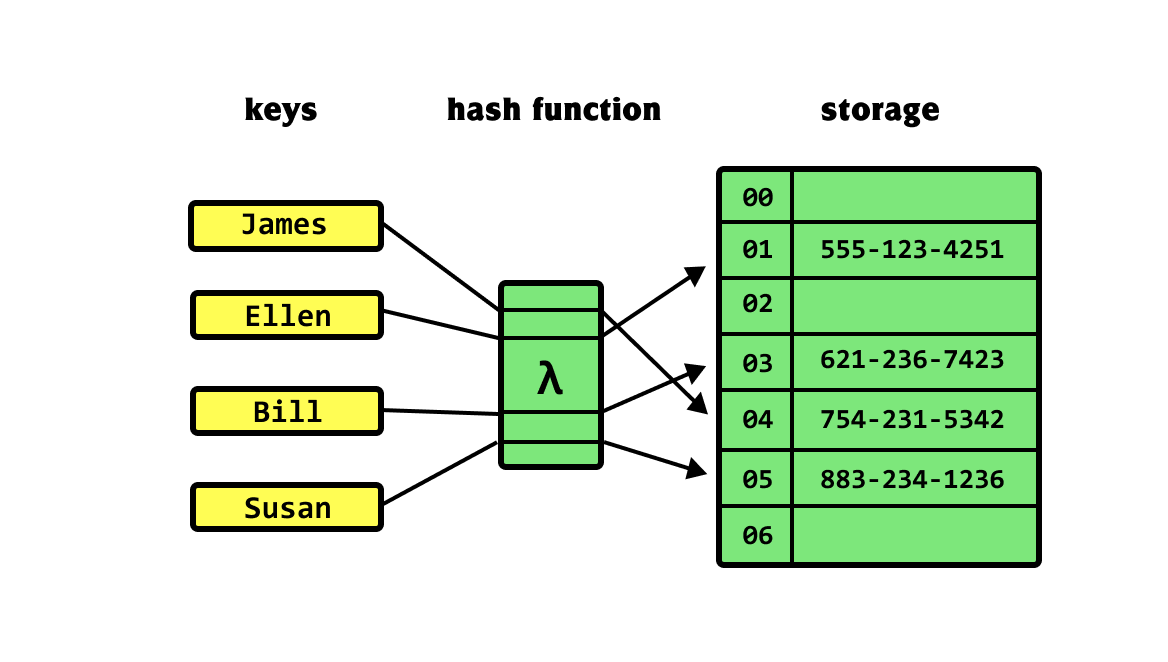

Source: https://khalilstemmler.com/img/blog/data-structures/hash-tables/hash-table.png

my_dictionary = {

# Key : Value

"Beer": "Bier",

"Apple": "Apfel",

"House": "Haus"

}

print(my_dictionary["House"])

Haus

d = {0: 1}

d[0]

1

keys-methodprint(my_dictionary.keys())

dict_keys(['Beer', 'Apple', 'House'])

value-methodprint(my_dictionary.values())

dict_values(['Bier', 'Apfel', 'Haus'])

items-methodprint(my_dictionary.items())

dict_items([('Beer', 'Bier'), ('Apple', 'Apfel'), ('House', 'Haus')])

Unlike, lists, tuples, or strings, dictionaries have no inherent order, meaning that it is not possible to access its contents via indexing or slicing.

Dictionaries help store a mapping from one unary element to another and are great for storing a collection of related data and using the keys as labels.

label_encoding = {

"Polite": 0,

"Mildly aggressive": 1,

"Aggressive": 2,

"Hateful": 3

}

print(label_encoding["Hateful"])

3

dataset = {

"x": [0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1],

"y": [0.5, 1.5, 0.5, 0.5, 1.5, 0.5, 1.5]

}

print(dataset["x"])

[0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1]

Booleans are the leanest datatype in Python. Their value range is restricted to two states: True and False

am_i_right = True

is_this_hard = False

Quiztime

True and False

True or False

not True

not False

print(0 < 1)

print(1 == 1)

print(0 > 1)

print(0 >= 1)

True True False False

Conditions make up one of the pillars of programming. They allow you to use Python not only as a calculator and to design your programs to detect and act on specific configurations of your data.

In Python there are four general types of conditions:

if-statements: Just act if a certain condition applies otherwise do nothing.# [Standard programm flow]

revenue = 1000

if revenue > 750:

print("What a good day!")

print("Go on!")

print("Closing the shop!")

# [Standard programm proceeds]

What a good day! Go on! Closing the shop!

if-else statements: Execute if-Clausel code if the condition is met, otherwise execute else-block# [Standard programm flow]

revenue = 1000

if revenue > 1500:

print("What a good day!")

else:

print("Alert, we should change somehting!")

# [Standard programm proceeds]

Alert, we should change somehting!

if-elif-elsestatements: Check on multiple conditions and execute the one that is met, otherwise execute else-blockrevenue = 867

if revenue < 500:

print("Horrendous day")

elif revenue > 500 and revenue < 750:

print("Bad day")

elif revenue > 750 and revenue < 1000:

print("We did okay")

else:

print("We did great")

We did okay

if-elif-else statements finish after the first true condition is met. If you want multiple conditions to be checked sequentially, you can chain various single if statements.text = "Hello\nmy mobile number is 01234\ngreetings Lennart"

words = text.lower().split()

politeness_score = 0

if words[0] in ["hello", "ciao", ...]:

# If there is a greeting, increase politeness score

politeness_score += 1

if words[-2] == "greetings":

# If there is a salute, also increase politeness score

politeness_score += 1

if "moron" in words:

# If there is an insult, we set politeness score to zero..

politeness_score = 0

print(f"Message:\n'{text}'\nachieved a politeness score of {politeness_score}")

Message: 'Hello my mobile number is 01234 greetings Lennart' achieved a politeness score of 2

Often your programs have to iteratively apply operations to your data to achieve the desired results. Python provides two types of loops to repeat operations.

For-loops serve two purposes:

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

my_new_list = []

for elem in my_list:

new_element = elem * 2

my_new_list.append(new_element)

print(my_new_list)

[2] [2, 4] [2, 4, 6]

for charachter in "Mobile number: 123":

print(charachter.isnumeric())

False False False False False False False False False False False False False False False True True True

x = 2

for run in range(8):

x = x * 2

print(x)

512

x = 10

while x > 0:

print(x)

x = x - 1

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

x = 10

while x > 0:

print(x)

x = x + 1

break-keywordfrom time import sleep

for i in range(10):

sleep(1)

do_continue = input("Do you want to keep on waiting for Godot? (y/n) ")

if do_continue.lower() in ("n", "no"):

print("Maybe he'll come tomorrow!")

break

Do you want to keep on waiting for Godot? (y/n) yes Do you want to keep on waiting for Godot? (y/n) no Maybe he'll come tomorrow!

do-while like loopsmy_number = 1

while True:

my_number += 1

if my_number >= 1:

break

print(my_number)

2